Wiki—January 1st, 2024

A language isolate is a language that has no demonstrable genetic relationship with another language.[1] Basque in Europe, Ainu in Asia, Sandawe in Africa, Haida and Zuni in North America, Kanoê in South America, and Tiwi in Australia are all examples of language isolates. The exact number of language isolates is yet unknown due to insufficient data on several languages.[2]

1. Campbell, Lyle (2010-08-24). "Language Isolates and Their History, or, What's Weird, Anyway?".Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society. 36(1): 16–31.

2. Cambell, Lyle (2018). "Introduction". Language Isolates edited by Lyle Campbell, pp. xi–xiv. Routledge.

Wiki—January 27th to February 2nd, 2020

In computing, data storage, and data transmission, character encoding is used to represent a repertoire of characters by some kind of encoding system.[1] Depending on the abstraction level and context, corresponding code points and the resulting code space may be regarded as bit patterns, octets, natural numbers, electrical pulses, etc. A character encoding is used in computation, data storage, and transmission of textual data. "Character set", "character map", "codeset" and "code page" are related, but not identical, terms.

1. Definition from The Tech Terms Dictionary.

Wiki—January 20th to 26th, 2020

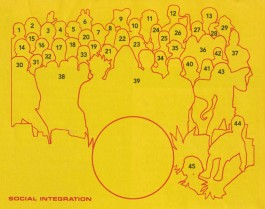

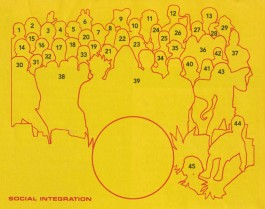

Folksonomy is a classification system in which end users apply public tags to online items, typically to make those items easier for themselves or others to find later. Over time, this can give rise to a classification system based on those tags and how often they are applied or searched for, in contrast to a taxonomic classification designed by the owners of the content and specified when it is published.[1][2] This practice is also known as collaborative tagging,[3][4] social classification, social indexing, and social tagging. Folksonomy was originally "the result of personal free tagging of information [...] for one's own retrieval",[5] but online sharing and interaction expanded it into collaborative forms.

1. Peters, Isabella (2005). "Folksonomies. Indexing and Retrieval in Web 2.0". Berlin: De Gruyter Saur. (isabella-peters.de)

2. Pink, Daniel H. (11 December 2005). "Folksonomy". New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

3. Lambiotte, R; Ausloos, M. (2005). Computational Science – ICCS 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 3993. pp. 1114-1117. arXiv:cs.DS/0512090. doi:10.1007/11758532_152. ISBN 978-3-540-34383-7.

4. Borne, Kirk. "Collaborative Annotation for Scientific Data Discovery and Reuse". Bulletin of Association for Information Science and Technology. ASIS&T. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

5. Vander Wal, Thomas (11 December 2005). "Folksonomy Coinage and Definition".

Wiki—January 13th to 19th, 2020

Bulk mail broadly refers to mail that is mailed and processed in bulk at reduced rates. The term is sometimes used as a synonym for advertising mail. The United States Postal Service (USPS) defines bulk mail broadly as "quantities of mail prepared for mailing at reduced postage rates." The preparation includes presorting and placing into containers by ZIP code. The containers, along with a manifest, are taken to an area in a post office called a bulk-mail-entry unit. The presorting and the use of containers allow highly automated mail processing, both in bulk and piecewise, in processing facilities called bulk mail centers (BMCs). In 2009, the USPS announced plans to streamline sorting and delivery. BMCs were renamed Network Distribution Centers.[1][2]

1. Postal Service to Revamp Bulk Mail Center Network Parcel, February 25 2009.

2. Changes In Store For Postal Bulk Mail Center Network PostalReporter News Blog, February 26 2009.

Wiki—January 6th to 12th, 2020

Because memory is not just an individual, private experience but is also part of the collective domain, cultural memory has become a topic in both historiography (Pierre Nora, Richard Terdiman) and cultural studies (e.g., Susan Stewart). These emphasize cultural memory’s process (historiography) and its implications and objects (cultural studies), respectively. Two schools of thought have emerged, one articulates that the present shapes our understanding of the past. The other assumes that the past has an influence on our present behavior.[1][2] It has, however, been pointed out (most notably by Guy Beiner) that these two approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive.[3]

1. Schwartz, Barry. 1991. "Social Change and Collective Memory: The Democratization of George Washington." American Sociological Review 56: 221-236.

2. Schwartz, B. (2010). 'Culture and Collective Memory: Two Comparative Perspectives'. In. Hall, J. R.; Grindstaff, L. and Lo, M-C. Handbook of Cultural Sociology. London: Routledge.

3. Guy Beiner, Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory (University of Wisconsin Press, 2007, pp. 29-30.

Wiki—December 30th, 2019 to January 5th, 2020

Linear B is a syllabic script that was used for writing Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1450 BC.[1] It is descended from the older Linear A, an undeciphered earlier script used for writing the Minoan language, as is the later Cypriot syllabary, which also recorded Greek. Linear B, found mainly in the palace archives at Knossos, Cydonia,[2] Pylos, Thebes and Mycenae,[3] disappeared with the fall of Mycenaean civilization during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The succeeding period, known as the Greek Dark Ages, provides no evidence of the use of writing. It is also the only one of the Bronze Age Aegean scripts to have been deciphered, by English architect and self-taught linguist Michael Ventris.[4]

1. "New Linear B tablet found at Iklaina". Comité International Permanent des Études Mycéniennes, UNESCO. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

2. Hogan, C. Michael (2008). "Cydonia". The Modern Antiquarian. Julian Cope. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

3. Wren, Linnea Holmer; Wren, David J.; Carter, Janine M. (1987). Perspectives on Western Art: Source Documents and Readings from the Ancient Near East Through the Middle Ages. Harper & Row. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-06-438942-6.

4. "Cracking the code: the decipherment of Linear B 60 years on". Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge. 13 October 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

Wiki—December 23rd to 29th, 2019

Gerald McBoing-Boing is an animated short film about a little boy who speaks through sound effects instead of spoken words. It was produced by United Productions of America (UPA) and given wide release by Columbia Pictures on November 2, 1950. It was adapted by Phil Eastman and Bill Scott from a story by Dr. Seuss, directed by Robert Cannon, and produced by John Hubley. Gerald McBoing-Boing won the 1950 Oscar for Best Animated Short,[1] Gerald McBoing-Boing is In 1994, it was voted #9 of The 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time by members of the animation field, making it the highest ranked UPA cartoon on the list. In 1995, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

1. Brody, Martin (2014-01-01). Music and Musical Composition at the American Academy in Rome. Boydell & Brewer. p. 53. ISBN 9781580462457.

Wiki—December 16th to 22nd, 2019

The Wiener Werkstätte (engl.: Vienna Workshop), established in 1903 by the graphic designer and painter Koloman Moser, the architect Josef Hoffmann and the patron Fritz Waerndorfer was a productive cooperative of artisans in Vienna, Austria bringing together architects, artists and designers working in ceramics, fashion, silver, furniture and the graphic arts.[1] It is regarded as a pioneer of modern design, and its influence can be seen in later styles such as Bauhaus and Art Deco.[2] Following World War I, the workshop was beset by financial troubles and material shortages. Attempts to expand the workshop's base were unsuccessful, and ultimately it was forced to close in 1932.

1. "The Vienna Secession: a History". theviennasecession.com. 2 June 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

2. Pevsner, Nikolaus (2005). Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. 4th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0300105711.

Wiki—December 9th to 15th, 2019

Cheating in online games is defined as the action of pretending to comply with the rules of the game, while secretly subverting them to gain an unfair advantage over an opponent.[1] Depending on the game, different activities constitute cheating and it is either a matter of game policy or consensus opinion as to whether a particular activity is considered to be cheating. Cheating reportedly exists in most multiplayer online games, but it is difficult to measure.[2] The Internet and darknets can provide players with the methodology necessary to cheat in online games, sometimes in return for a price.

1. Clive Thompson (2007-04-23). "What Type of Game Cheater Are You?". Wired.com. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

2. "How to Hurt the Hackers: "The Scoop on Internet Cheating and How You Can Combat It"". Gamasutra.com. 2000-07-24. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

WIP—December 2nd to 8th, 2019

1. 12052019_ImagesFinals-16A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

2. 12052019_ImagesFinals-14A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

3. 12052019_ImagesFinals-18A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

4. 12052019_ImagesFinals-23A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

Wiki—November 25th to December 1st, 2019

The year 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer (also the Poverty Year and Eighteen Hundred and Froze To Death)[1] because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by 0.4–0.7 °C (0.72–1.26 °F).[2] This resulted in major food shortages across the Northern Hemisphere.[3]

1. "Weather Doctor's Weather People and History: Eighteen Hundred and Froze To Death, The Year There Was No Summer". Islandnet.com. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

2. Stothers, Richard B. (1984). "The Great Tambora Eruption in 1815 and Its Aftermath". Science. 224 (4654): 1191–1198. Bibcode:1984Sci...224.1191S.

3. "Saint John New Brunswick Time Date". New-brunswick.net. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

WIP—November 18th to 24th, 2019

1. collages_nov22-05.jpg. 1080x1080. November 22 12:17.

2. collages_nov22-06.jpg. 1080x1080. November 22 12:17.

3. collages_nov22-07.jpg. 1080x1080. November 22 12:17.

4. collages_nov22-08.jpg. 1080x851. November 22 12:17.

Wiki—November 10th to 17th, 2019

In computing, time-sharing is the sharing of a computing resource among many users by means of multiprogramming and multi-tasking at the same time.[1] Its emergence as the prominent model of computing in the 1970s represented a major technological shift in the history of computing. By allowing many users to interact concurrently with a single computer, time-sharing dramatically lowered the cost of providing computing capability, made it possible for individuals and organizations to use a computer without owning one,[2] and promoted the interactive use of computers and the development of new interactive applications.

1. DEC TIMESHARING (1965), by Peter Clark, The DEC Professional, VOLUME 1, Number 1.

2. IBM advertised, early 1960s, with a headline: "This man is sharing a $2 million computer".

WIP—November 3rd to 9th, 2019

1. CEMEL - Clothing, Women's Service, Hat (Experimental). September 4 1975.

2. IPL Sleeping Bag. October 15 1984.

3. One Piece Cover All - Movement Panel. April 20 1978.

Wiki—October 27th to November 2nd, 2019

A chatbot is a piece of software that conducts a conversation via auditory or textual methods.[1] Such programs are often designed to convincingly simulate how a human would behave as a conversational partner, although as of 2019, they are far short of being able to pass the Turing test.[2] Chatbots are typically used in dialog systems for various practical purposes including customer service or information acquisition. Some chatbots use sophisticated natural language processing systems, but many simpler ones scan for keywords within the input, then pull a reply with the most matching keywords, or the most similar wording pattern, from a database.

1. "What is a chatbot?". techtarget.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

2. Luka Bradeško, Dunja Mladenić. "A Survey of Chabot Systems through a Loebner Prize Competition" (PDF). Retrieved 28 June 2019.

Wiki—October 20th to 26th, 2019

Subject indexing is the act of describing or classifying a document by index terms or other symbols in order to indicate what the document is about, to summarize its content or to increase its findability. In other words, it is about identifying and describing the subject of documents. Indexes are constructed, separately, on three distinct levels: terms in a document such as a book; objects in a collection such as a library; and documents (such as books and articles) within a field of knowledge. Subject indexing is used in information retrieval especially to create bibliographic indexes to retrieve documents on a particular subject. Examples of academic indexing services are Zentralblatt MATH, Chemical Abstracts and PubMed. The index terms were mostly assigned by experts but author keywords are also common. The process of indexing begins with any analysis of the subject of the document. The indexer must then identify terms which appropriately identify the subject either by extracting words directly from the document or assigning words from a controlled vocabulary.[1] The terms in the index are then presented in a systematic order. Indexers must decide how many terms to include and how specific the terms should be. Together this gives a depth of indexing.

1. F. W. Lancaster (2003): "Indexing and abstracting in theory and practise". Third edition. London, Facet ISBN 1-85604-482-3. Page 6.

Wiki—October 13th to 19th, 2019

The Wheel of Death, in the context of acrobatic circus arts, is a large rotating apparatus on which performers carry out synchronized acrobatic skills. The "wheel" is actually a large space frame beam with hooped tracks at either end, within which the performers can stand. As the performers run around on either the inside or outside of the hoops, the whole apparatus rotates. Performers also perform balancing skills with the wheel in a stationary position. The Wheel of Death is said to have originated in America during the early 1930s and was also known as the Space Wheel. Some early versions were performed by a single artist and incorporated a counterbalance on the other end. Following fatal accidents, the apparatus fell out of favour for a time until it was re-introduced in the 1970s under the name Wheel of Death.[1] For its 2007 touring edition, Ringling Bros. started using the name Wheel of Steel, as the word death was not seen as family friendly from a public relations perspective.[2]

1. "The Wheel of Death". G. A. Bungee. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

2. Collins, Glenn (2007-03-30). "With the Greatest of Ease". The New York Times.

Wiki—October 6th to 12th, 2019

Scanlan's Monthly was a short-lived monthly publication, which ran from March 1970 to January 1971.[1] The publisher was Scanlan's Literary House.[2] Edited by Warren Hinckle III and Sidney Zion, it featured politically controversial muckraking and was ultimately subject to an investigation by the FBI during the Nixon administration.[1] It was boycotted by printers as "un-American" by 1971. According to the publishers more than 50 printers refused to handle the January 1971 special issue Guerilla War in the USA because it appeared to be promoting domestic terrorism. The issue was finally printed in Quebec and in a German translation in Stuttgart (Guerilla-Krieg in USA, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt 1971). The magazine produced a total of eight issues during its existence.[3]

1. "Hunter S. Thompson in Scanlans Magazine". HST Books. 24 November 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

2. "Product Details". Amazon. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

3. "Scanlan's Monthly". SVA Library Picture and Periodicals Collection. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

Wiki—September 29th to October 5th, 2019

A simulacrum (plural: simulacra from Latin: simulacrum, which means "likeness, similarity") is a representation or imitation of a person or thing.[1] The word was first recorded in the English language in the late 16th century, used to describe a representation, such as a statue or a painting, especially of a god. By the late 19th century, it had gathered a secondary association of inferiority: an image without the substance or qualities of the original.[2] Literary critic Fredric Jameson offers photorealism as an example of artistic simulacrum, where a painting is sometimes created by copying a photograph that is itself a copy of the real.[3]

1. "Word of the Day". dictionary.com. 1 May 2003. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

2. "simulacrum" The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary 1993.

3. Massumi, Brian. "Realer than Real: The Simulacrum According to Deleuze and Guattari." Archived 23 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 2 May 2007.

Wiki—September 22nd to 28th, 2019

Images and other stimuli contain both local features (details, parts) and global features (the whole). Precedence refers to the level of processing (global or local) to which attention is first directed.[1] Global precedence occurs when an individual more readily identifies the global feature when presented with a stimulus containing both global and local features.[2] The global aspect of an object embodies the larger, overall image as a whole, whereas the local aspect consists of the individual features that make up this larger whole. Global processing is the act of processing a visual stimulus holistically. Although global precedence is generally more prevalent than local precedence, local preference also occurs under certain circumstances and for certain individuals.[3] Global precedence is closely related to the Gestalt principles of grouping in that the global whole is a grouping of proximal and similar objects. Within global precedence, there is also the global interference effect, which occurs when an individual is directed to identify the local characteristic, and the global characteristic subsequently interferes by slowing the reaction time.

1. Hayward DA, Shore DI, Ristic J, Kovshoff H, Iarocci G, Mottron L, Burack JA (November 2012). "Flexible visual processing in young adults with autism: the effects of implicit learning on a global-local task" (PDF). J Autism Dev Disord. 42 (11): 2383–2392. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1485-0. PMID 22391810.

2. Navon, D. (Jul 1977). "Forest before trees: The precedence of global features in visual perception". Cognitive Psychology. 9 (3): 353–383. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(77)90012-3.

3. Davidoff, J.; E. Fonteneau; J. Fagot (Sep 2008). "Local and global processing: Observations from a remote culture". Cognition. 108 (3): 702-709. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2008.06.004. PMID 18662813.

Wiki—September 15th to 21st, 2019

Creative Computing was one of the earliest magazines covering the microcomputer revolution. Published from October 1974 until October 1985, the magazine covered the spectrum of hobbyist, home, and personal computing in a more accessible format than the rather technically oriented BYTE.[1] Creative Computing also published software on cassette tape and floppy disk for the popular computer systems of the time.

1. "Creative Computing". The Online Books Page: Serial Archive Listings. USA: University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

Wiki—September 8th to 14th, 2019

Asemic writing is a wordless open semantic form of writing.[1][2][3] The word asemic means "having no specific semantic content", or "without the smallest unit of meaning".[4] With the non-specificity of asemic writing there comes a vacuum of meaning, which is left for the reader to fill in and interpret. All of this is similar to the way one would deduce meaning from an abstract work of art. Where asemic writing differs from abstract art is in the asemic author's use of gestural constraint, and the retention of physical characteristics of writing such as lines and symbols. Asemic writing is a hybrid art form that fuses text and image into a unity, and then sets it free to arbitrary subjective interpretations. It may be compared to free writing or writing for its own sake, instead of writing to produce verbal context.

1. Michael Jacobson. "Works & Interviews". Post-Asemic Press.

2. "Tim Gaze". Asemic Magazine.

3. "Full Of Crow Tim Gaze interview". Full of Crow.

4. From Greek: asemos (αόεμoβ) = without sign, unmarked, obscure, or ignoble.

Field Notes—September 1st to 7th, 2019

1. Paris - 11th arr. (2019). September 1 10:30 PM.

2. Tuileries Garden (2019). September 2 1:25 PM.

3. Paris - Les Grand Boulevards (2019). September 2 12:01 AM.

4. Air France AF 10 (2019). September 4 7:16 PM.

Field Notes—August 25th to 31st, 2019

1. Biarritz (2019). August 27 8:22 PM.

2. Biarritz (2019). August 28 12:50 PM.

3. Biarritz (2019). August 29 9:11 PM.

4. Benon (2019). August 29 5:05 PM.

5. Courçon (2019). August 29 8:10 PM.

Field Notes—August 18th to 24th, 2019

1. Sanilhac-Sagriès (2019). August 22 6:50 PM.

2. Uzès (2019). August 24 12:10 PM.

3. Montaren-en-Saint-Médiers (2019). August 24 7:31 PM

4. Montaren-en-Saint-Médiers (2019). August 24 7:36 PM.

Wiki—August 11th to 17th, 2019

The coastline paradox is the counterintuitive observation that the coastline of a landmass does not have a well-defined length. This results from the fractal-like properties of coastlines, i.e., the fact that a coastline typically has a fractal dimension (which in fact makes the notion of length inapplicable). The first recorded observation of this phenomenon was by Lewis Fry Richardson[1] and it was expanded upon by Benoit Mandelbrot.[2]

1. Weisstein, Eric W. "Coastline Paradox". MathWorld.

2. Mandelbrot, Benoit (1983). The Fractal Geometry of Nature. W.H. Freeman and Co. 25–33. ISBN 978-0-7167-1186-5.

Wiki—August 4th to 10th, 2019

Blobitecture (from blob architecture), blobism and blobismus are terms for a movement in architecture in which buildings have an organic, amoeba-shaped, building form.[1] Though the term 'blob architecture' was in vogue already in the mid-1990s, the word blobitecture first appeared in print in 2002, in William Safire's "On Language" column in the New York Times Magazine in an article entitled Defenestration.[2] Though intended in the article to have a derogatory meaning, the word stuck and is often used to describe buildings with curved and rounded shapes.

1. Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback) (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 880 pages. ISBN 0-19-860678-8.

2. Safire, Wiliam. The New York Times: On Language. Defenestration. December 1, 2002.

Wiki—July 28th to August 3rd, 2019

In machine learning, feature learning or representation learning[1] is a set of techniques that allows a system to automatically discover the representations needed for feature detection or classification from raw data. This replaces manual feature engineering and allows a machine to both learn the features and use them to perform a specific task.

1. Y. Bengio; A. Courville; P. Vincent (2013). "Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives". IEEE Trans. PAMI, special issue Learning Deep Architectures. 35: 1798-1828. arXiv:1206.5538. doj:10.1109/tpami.2013.50.

Wiki—January 27th to February 2nd, 2020

In computing, data storage, and data transmission, character encoding is used to represent a repertoire of characters by some kind of encoding system.[1] Depending on the abstraction level and context, corresponding code points and the resulting code space may be regarded as bit patterns, octets, natural numbers, electrical pulses, etc. A character encoding is used in computation, data storage, and transmission of textual data. "Character set", "character map", "codeset" and "code page" are related, but not identical, terms.

1. Definition from The Tech Terms Dictionary.

Wiki—January 20th to 26th, 2020

Folksonomy is a classification system in which end users apply public tags to online items, typically to make those items easier for themselves or others to find later. Over time, this can give rise to a classification system based on those tags and how often they are applied or searched for, in contrast to a taxonomic classification designed by the owners of the content and specified when it is published.[1][2] This practice is also known as collaborative tagging,[3][4] social classification, social indexing, and social tagging. Folksonomy was originally "the result of personal free tagging of information [...] for one's own retrieval",[5] but online sharing and interaction expanded it into collaborative forms.

1. Peters, Isabella (2005). "Folksonomies. Indexing and Retrieval in Web 2.0". Berlin: De Gruyter Saur. (isabella-peters.de)

2. Pink, Daniel H. (11 December 2005). "Folksonomy". New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

3. Lambiotte, R; Ausloos, M. (2005). Computational Science – ICCS 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 3993. pp. 1114-1117. arXiv:cs.DS/0512090. doi:10.1007/11758532_152. ISBN 978-3-540-34383-7.

4. Borne, Kirk. "Collaborative Annotation for Scientific Data Discovery and Reuse". Bulletin of Association for Information Science and Technology. ASIS&T. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

5. Vander Wal, Thomas (11 December 2005). "Folksonomy Coinage and Definition".

Wiki—January 13th to 19th, 2020

Bulk mail broadly refers to mail that is mailed and processed in bulk at reduced rates. The term is sometimes used as a synonym for advertising mail. The United States Postal Service (USPS) defines bulk mail broadly as "quantities of mail prepared for mailing at reduced postage rates." The preparation includes presorting and placing into containers by ZIP code. The containers, along with a manifest, are taken to an area in a post office called a bulk-mail-entry unit. The presorting and the use of containers allow highly automated mail processing, both in bulk and piecewise, in processing facilities called bulk mail centers (BMCs). In 2009, the USPS announced plans to streamline sorting and delivery. BMCs were renamed Network Distribution Centers.[1][2]

1. Postal Service to Revamp Bulk Mail Center Network Parcel, February 25 2009.

2. Changes In Store For Postal Bulk Mail Center Network PostalReporter News Blog, February 26 2009.

Wiki—January 6th to 12th, 2020

Because memory is not just an individual, private experience but is also part of the collective domain, cultural memory has become a topic in both historiography (Pierre Nora, Richard Terdiman) and cultural studies (e.g., Susan Stewart). These emphasize cultural memory’s process (historiography) and its implications and objects (cultural studies), respectively. Two schools of thought have emerged, one articulates that the present shapes our understanding of the past. The other assumes that the past has an influence on our present behavior.[1][2] It has, however, been pointed out (most notably by Guy Beiner) that these two approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive.[3]

1. Schwartz, Barry. 1991. "Social Change and Collective Memory: The Democratization of George Washington." American Sociological Review 56: 221-236.

2. Schwartz, B. (2010). 'Culture and Collective Memory: Two Comparative Perspectives'. In. Hall, J. R.; Grindstaff, L. and Lo, M-C. Handbook of Cultural Sociology. London: Routledge.

3. Guy Beiner, Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory (University of Wisconsin Press, 2007, pp. 29-30.

Wiki—December 30th, 2019 to January 5th, 2020

Linear B is a syllabic script that was used for writing Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of Greek. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries. The oldest Mycenaean writing dates to about 1450 BC.[1] It is descended from the older Linear A, an undeciphered earlier script used for writing the Minoan language, as is the later Cypriot syllabary, which also recorded Greek. Linear B, found mainly in the palace archives at Knossos, Cydonia,[2] Pylos, Thebes and Mycenae,[3] disappeared with the fall of Mycenaean civilization during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The succeeding period, known as the Greek Dark Ages, provides no evidence of the use of writing. It is also the only one of the Bronze Age Aegean scripts to have been deciphered, by English architect and self-taught linguist Michael Ventris.[4]

1. "New Linear B tablet found at Iklaina". Comité International Permanent des Études Mycéniennes, UNESCO. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

2. Hogan, C. Michael (2008). "Cydonia". The Modern Antiquarian. Julian Cope. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

3. Wren, Linnea Holmer; Wren, David J.; Carter, Janine M. (1987). Perspectives on Western Art: Source Documents and Readings from the Ancient Near East Through the Middle Ages. Harper & Row. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-06-438942-6.

4. "Cracking the code: the decipherment of Linear B 60 years on". Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge. 13 October 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

Wiki—December 23rd to 29th, 2019

Gerald McBoing-Boing is an animated short film about a little boy who speaks through sound effects instead of spoken words. It was produced by United Productions of America (UPA) and given wide release by Columbia Pictures on November 2, 1950. It was adapted by Phil Eastman and Bill Scott from a story by Dr. Seuss, directed by Robert Cannon, and produced by John Hubley. Gerald McBoing-Boing won the 1950 Oscar for Best Animated Short,[1] Gerald McBoing-Boing is In 1994, it was voted #9 of The 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time by members of the animation field, making it the highest ranked UPA cartoon on the list. In 1995, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

1. Brody, Martin (2014-01-01). Music and Musical Composition at the American Academy in Rome. Boydell & Brewer. p. 53. ISBN 9781580462457.

Wiki—December 16th to 22nd, 2019

The Wiener Werkstätte (engl.: Vienna Workshop), established in 1903 by the graphic designer and painter Koloman Moser, the architect Josef Hoffmann and the patron Fritz Waerndorfer was a productive cooperative of artisans in Vienna, Austria bringing together architects, artists and designers working in ceramics, fashion, silver, furniture and the graphic arts.[1] It is regarded as a pioneer of modern design, and its influence can be seen in later styles such as Bauhaus and Art Deco.[2] Following World War I, the workshop was beset by financial troubles and material shortages. Attempts to expand the workshop's base were unsuccessful, and ultimately it was forced to close in 1932.

1. "The Vienna Secession: a History". theviennasecession.com. 2 June 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

2. Pevsner, Nikolaus (2005). Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius. 4th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 164. ISBN 0300105711.

Wiki—December 9th to 15th, 2019

Cheating in online games is defined as the action of pretending to comply with the rules of the game, while secretly subverting them to gain an unfair advantage over an opponent.[1] Depending on the game, different activities constitute cheating and it is either a matter of game policy or consensus opinion as to whether a particular activity is considered to be cheating. Cheating reportedly exists in most multiplayer online games, but it is difficult to measure.[2] The Internet and darknets can provide players with the methodology necessary to cheat in online games, sometimes in return for a price.

1. Clive Thompson (2007-04-23). "What Type of Game Cheater Are You?". Wired.com. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

2. "How to Hurt the Hackers: "The Scoop on Internet Cheating and How You Can Combat It"". Gamasutra.com. 2000-07-24. Retrieved 2009-09-15.

WIP—December 2nd to 9th, 2019

1. 12052019_ImagesFinals-16A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

2. 12052019_ImagesFinals-14A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

3. 12052019_ImagesFinals-18A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

4. 12052019_ImagesFinals-23A.jpg. 1080x1080. December 6 4:12.

Wiki—November 25th to December 1st, 2019

The year 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer (also the Poverty Year and Eighteen Hundred and Froze To Death)[1] because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by 0.4–0.7 °C (0.72–1.26 °F).[2] This resulted in major food shortages across the Northern Hemisphere.[3]

1. "Weather Doctor's Weather People and History: Eighteen Hundred and Froze To Death, The Year There Was No Summer". Islandnet.com. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

2. Stothers, Richard B. (1984). "The Great Tambora Eruption in 1815 and Its Aftermath". Science. 224 (4654): 1191–1198. Bibcode:1984Sci...224.1191S.

3. "Saint John New Brunswick Time Date". New-brunswick.net. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

WIP—November 18th to 24th, 2019

1. collages_nov22-05.jpg. 1080x1080. November 22 12:17.

2. collages_nov22-06.jpg. 1080x1080. November 22 12:17.

3. collages_nov22-07.jpg. 1080x1080. November 22 12:17.

4. collages_nov22-08.jpg. 1080x851. November 22 12:17.

Wiki—November 10th to 17th, 2019

In computing, time-sharing is the sharing of a computing resource among many users by means of multiprogramming and multi-tasking at the same time.[1] Its emergence as the prominent model of computing in the 1970s represented a major technological shift in the history of computing. By allowing many users to interact concurrently with a single computer, time-sharing dramatically lowered the cost of providing computing capability, made it possible for individuals and organizations to use a computer without owning one,[2] and promoted the interactive use of computers and the development of new interactive applications.

1. DEC TIMESHARING (1965), by Peter Clark, The DEC Professional, VOLUME 1, Number 1.

2. IBM advertised, early 1960s, with a headline: "This man is sharing a $2 million computer".

WIP—November 3rd to 9th, 2019

1. CEMEL - Clothing, Women's Service, Hat (Experimental). September 4 1975.

2. IPL Sleeping Bag. October 15 1984.

3. One Piece Cover All - Movement Panel. April 20 1978.

Wiki—October 27th to November 2nd, 2019

A chatbot is a piece of software that conducts a conversation via auditory or textual methods.[1] Such programs are often designed to convincingly simulate how a human would behave as a conversational partner, although as of 2019, they are far short of being able to pass the Turing test.[2] Chatbots are typically used in dialog systems for various practical purposes including customer service or information acquisition. Some chatbots use sophisticated natural language processing systems, but many simpler ones scan for keywords within the input, then pull a reply with the most matching keywords, or the most similar wording pattern, from a database.

1. "What is a chatbot?". techtarget.com. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

2. Luka Bradeško, Dunja Mladenić. "A Survey of Chabot Systems through a Loebner Prize Competition" (PDF). Retrieved 28 June 2019.

Wiki—October 20th to 26th, 2019

Subject indexing is the act of describing or classifying a document by index terms or other symbols in order to indicate what the document is about, to summarize its content or to increase its findability. In other words, it is about identifying and describing the subject of documents. Indexes are constructed, separately, on three distinct levels: terms in a document such as a book; objects in a collection such as a library; and documents (such as books and articles) within a field of knowledge. Subject indexing is used in information retrieval especially to create bibliographic indexes to retrieve documents on a particular subject. Examples of academic indexing services are Zentralblatt MATH, Chemical Abstracts and PubMed. The index terms were mostly assigned by experts but author keywords are also common. The process of indexing begins with any analysis of the subject of the document. The indexer must then identify terms which appropriately identify the subject either by extracting words directly from the document or assigning words from a controlled vocabulary.[1] The terms in the index are then presented in a systematic order. Indexers must decide how many terms to include and how specific the terms should be. Together this gives a depth of indexing.

1. F. W. Lancaster (2003): "Indexing and abstracting in theory and practise". Third edition. London, Facet ISBN 1-85604-482-3. Page 6.

Wiki—October 13th to 19th, 2019

The Wheel of Death, in the context of acrobatic circus arts, is a large rotating apparatus on which performers carry out synchronized acrobatic skills. The "wheel" is actually a large space frame beam with hooped tracks at either end, within which the performers can stand. As the performers run around on either the inside or outside of the hoops, the whole apparatus rotates. Performers also perform balancing skills with the wheel in a stationary position. The Wheel of Death is said to have originated in America during the early 1930s and was also known as the Space Wheel. Some early versions were performed by a single artist and incorporated a counterbalance on the other end. Following fatal accidents, the apparatus fell out of favour for a time until it was re-introduced in the 1970s under the name Wheel of Death.[1] For its 2007 touring edition, Ringling Bros. started using the name Wheel of Steel, as the word death was not seen as family friendly from a public relations perspective.[2]

1. "The Wheel of Death". G. A. Bungee. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

2. Collins, Glenn (2007-03-30). "With the Greatest of Ease". The New York Times.

Wiki—October 6th to 12th, 2019

Scanlan's Monthly was a short-lived monthly publication, which ran from March 1970 to January 1971.[1] The publisher was Scanlan's Literary House.[2] Edited by Warren Hinckle III and Sidney Zion, it featured politically controversial muckraking and was ultimately subject to an investigation by the FBI during the Nixon administration.[1] It was boycotted by printers as "un-American" by 1971. According to the publishers more than 50 printers refused to handle the January 1971 special issue Guerilla War in the USA because it appeared to be promoting domestic terrorism. The issue was finally printed in Quebec and in a German translation in Stuttgart (Guerilla-Krieg in USA, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt 1971). The magazine produced a total of eight issues during its existence.[3]

1. "Hunter S. Thompson in Scanlans Magazine". HST Books. 24 November 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

2. "Product Details". Amazon. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

3. "Scanlan's Monthly". SVA Library Picture and Periodicals Collection. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

Wiki—September 29th to October 5th, 2019

A simulacrum (plural: simulacra from Latin: simulacrum, which means "likeness, similarity") is a representation or imitation of a person or thing.[1] The word was first recorded in the English language in the late 16th century, used to describe a representation, such as a statue or a painting, especially of a god. By the late 19th century, it had gathered a secondary association of inferiority: an image without the substance or qualities of the original.[2] Literary critic Fredric Jameson offers photorealism as an example of artistic simulacrum, where a painting is sometimes created by copying a photograph that is itself a copy of the real.[3]

1. "Word of the Day". dictionary.com. 1 May 2003. Archived from the original on 17 February 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2007.

2. "simulacrum" The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary 1993.

3. Massumi, Brian. "Realer than Real: The Simulacrum According to Deleuze and Guattari." Archived 23 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 2 May 2007.

Wiki—September 22nd to 28th, 2019

Images and other stimuli contain both local features (details, parts) and global features (the whole). Precedence refers to the level of processing (global or local) to which attention is first directed.[1] Global precedence occurs when an individual more readily identifies the global feature when presented with a stimulus containing both global and local features.[2] The global aspect of an object embodies the larger, overall image as a whole, whereas the local aspect consists of the individual features that make up this larger whole. Global processing is the act of processing a visual stimulus holistically. Although global precedence is generally more prevalent than local precedence, local preference also occurs under certain circumstances and for certain individuals.[3] Global precedence is closely related to the Gestalt principles of grouping in that the global whole is a grouping of proximal and similar objects. Within global precedence, there is also the global interference effect, which occurs when an individual is directed to identify the local characteristic, and the global characteristic subsequently interferes by slowing the reaction time.

1. Hayward DA, Shore DI, Ristic J, Kovshoff H, Iarocci G, Mottron L, Burack JA (November 2012). "Flexible visual processing in young adults with autism: the effects of implicit learning on a global-local task" (PDF). J Autism Dev Disord. 42 (11): 2383–2392. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1485-0. PMID 22391810.

2. Navon, D. (Jul 1977). "Forest before trees: The precedence of global features in visual perception". Cognitive Psychology. 9 (3): 353–383. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(77)90012-3.

3. Davidoff, J.; E. Fonteneau; J. Fagot (Sep 2008). "Local and global processing: Observations from a remote culture". Cognition. 108 (3): 702-709. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2008.06.004. PMID 18662813.

Wiki—September 15th to 21st, 2019

Creative Computing was one of the earliest magazines covering the microcomputer revolution. Published from October 1974 until October 1985, the magazine covered the spectrum of hobbyist, home, and personal computing in a more accessible format than the rather technically oriented BYTE.[1] Creative Computing also published software on cassette tape and floppy disk for the popular computer systems of the time.

1. "Creative Computing". The Online Books Page: Serial Archive Listings. USA: University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

Wiki—September 8th to 14th, 2019

Asemic writing is a wordless open semantic form of writing.[1][2][3] The word asemic means "having no specific semantic content", or "without the smallest unit of meaning".[4] With the non-specificity of asemic writing there comes a vacuum of meaning, which is left for the reader to fill in and interpret. All of this is similar to the way one would deduce meaning from an abstract work of art. Where asemic writing differs from abstract art is in the asemic author's use of gestural constraint, and the retention of physical characteristics of writing such as lines and symbols. Asemic writing is a hybrid art form that fuses text and image into a unity, and then sets it free to arbitrary subjective interpretations. It may be compared to free writing or writing for its own sake, instead of writing to produce verbal context.

1. Michael Jacobson. "Works & Interviews". Post-Asemic Press.

2. "Tim Gaze". Asemic Magazine.

3. "Full Of Crow Tim Gaze interview". Full of Crow.

4. From Greek: asemos (αόεμoβ) = without sign, unmarked, obscure, or ignoble.

Field Notes—September 1st to 7th, 2019

1. Paris - 11th arr. (2019). September 1 10:30 PM.

2. Tuileries Garden (2019). September 2 1:25 PM.

3. Paris - Les Grand Boulevards (2019). September 2 12:01 AM.

4. Air France AF 10 (2019). September 4 7:16 PM.

Field Notes—August 25th to 31st, 2019

1. Biarritz (2019). August 27 8:22 PM.

2. Biarritz (2019). August 28 12:50 PM.

3. Biarritz (2019). August 29 9:11 PM.

4. Benon (2019). August 29 5:05 PM.

5. Courçon (2019). August 29 8:10 PM.

Field Notes—August 18th to 24th, 2019

1. Sanilhac-Sagriès (2019). August 22 6:50 PM.

2. Uzès (2019). August 24 12:10 PM.

3. Montaren-en-Saint-Médiers (2019). August 24 7:31 PM

4. Montaren-en-Saint-Médiers (2019). August 24 7:36 PM.

Wiki—August 11th to 17th, 2019

The coastline paradox is the counterintuitive observation that the coastline of a landmass does not have a well-defined length. This results from the fractal-like properties of coastlines, i.e., the fact that a coastline typically has a fractal dimension (which in fact makes the notion of length inapplicable). The first recorded observation of this phenomenon was by Lewis Fry Richardson[1] and it was expanded upon by Benoit Mandelbrot.[2]

1. Weisstein, Eric W. "Coastline Paradox". MathWorld.

2. Mandelbrot, Benoit (1983). The Fractal Geometry of Nature. W.H. Freeman and Co. 25–33. ISBN 978-0-7167-1186-5.

Wiki—August 4th to 10th, 2019

Blobitecture (from blob architecture), blobism and blobismus are terms for a movement in architecture in which buildings have an organic, amoeba-shaped, building form.[1] Though the term 'blob architecture' was in vogue already in the mid-1990s, the word blobitecture first appeared in print in 2002, in William Safire's "On Language" column in the New York Times Magazine in an article entitled Defenestration.[2] Though intended in the article to have a derogatory meaning, the word stuck and is often used to describe buildings with curved and rounded shapes.

1. Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback) (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 880 pages. ISBN 0-19-860678-8.

2. Safire, Wiliam. The New York Times: On Language. Defenestration. December 1, 2002.

Wiki—July 28th to August 3rd, 2019

In machine learning, feature learning or representation learning[1] is a set of techniques that allows a system to automatically discover the representations needed for feature detection or classification from raw data. This replaces manual feature engineering and allows a machine to both learn the features and use them to perform a specific task.

1. Y. Bengio; A. Courville; P. Vincent (2013). "Representation Learning: A Review and New Perspectives". IEEE Trans. PAMI, special issue Learning Deep Architectures. 35: 1798-1828. arXiv:1206.5538. doj:10.1109/tpami.2013.50.